Is soil carbon sequestration a ready climate solution?

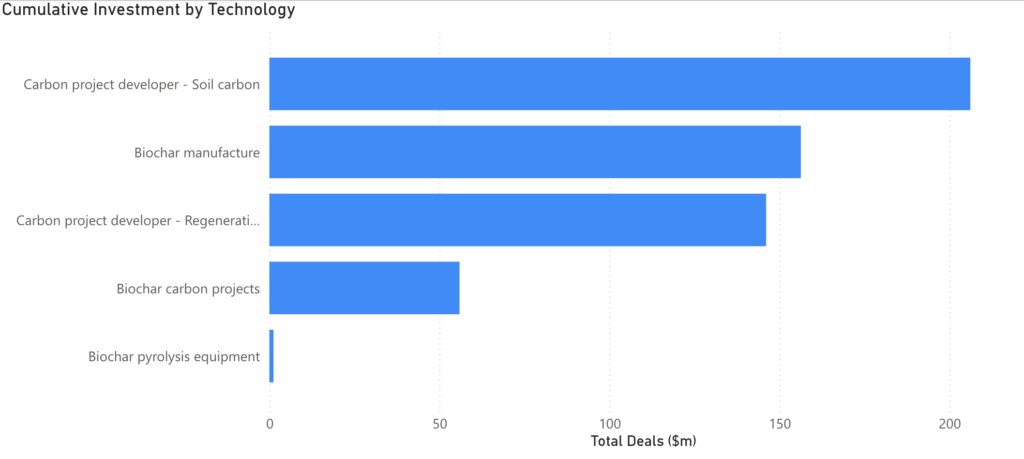

Figure 1. Investment in soil sequestration companies: Carbon offset developers and Biochar manufacturers (excl Indigo)

As climate change continues at pace, and the world struggles to cut annual emissions, there is a growing focus and premium on removing carbon from the atmosphere, rather than simply emitting less, where soil carbon sequestation is getting growing attention.

At present, there are limited proven technologies for carbon removal at scale, where the most obvious is tree planting.

One additional approach is to sequester carbon in the soil. Hurdles to date have included the expense of measuring soil carbon. In a recent insight, we called out some leading companies overcoming that problem, such as Yard Stick, EarthOptics, Perennial, Agricarbon and Chrysalabs.

We see two key approaches at present for monetising soil carbon sequestration: first, carbon offset generation, for example by encouraging regenerative farming practices, and second, manufacture of biochar (see Figure 1 above, which excludes the outlier, Indigo).

Regenerative farming seeks to build soil organic matter, and so soil carbon, through practices like cover cropping, under-sowing and direct drilling. Carbon project developers are emerging, that focus on generating carbon offsets by advising farmers to undertake such practices, and implementing the project validation and verification required to generate bona fide credits.

The world’s biggest agricultural carbon credit developer is Indigo, which has raised $2.16 billion to date, including $270 million in January. Indigo has three core businesses: carbon credit generation; sustainable crop inputs; and e-commerce. Indigo helps farmers generate carbon credits through regenerative farm practices, validated under its own carbon standard. The world’s biggest “pure-play” soil carbon credit developer, meanwhile, is Agreena.

Our second key carbon monetisation approach to date is biochar manufacture, which involves the anaerobic heating, or pyrolysis, of woody biomass, to produce a stable form of pure carbon. The resulting so-called biochar can be mixed into the soil, both to sequester carbon, and as a soil amendment, which may improve soil structure and lock in moisture.

The world’s biggest biochar manufacturer by investment to date is Airex Energy, an industrial-scale producer of biochar, and other products, from sawmills and from woody biomass, for use as a soil amendment in agriculture, and for energy sector applications, as an alternative to coal.

Credit for this week’s insight goes to Jerry Nelson, emeritus professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who was the interviewee in our latest podcast, published this week.

Jerry is a former lead author at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), with a focus on climate-smart agriculture. Jerry describes serious climate risks facing the global food sector, in an era of climate change, pointing especially to the problem of heat impacts, where scientists have had little to zero success so far, developing heat tolerant (as opposed to drought tolerant) varieties of food staples.

Living in the high desert in the United States, he found biochar was a promising approach to storing water in the soil, to address the climate adaptation problem.

“Biochar can hold water, and quite a lot of water as it turns out. The challenge is making the stuff, at large scale, but I still think it has a lot of promise, especially in desert areas like we’re in,” he told us.